Typographical Banality and the Univocal Mind

In recent years, a number of global brands—including everything from Yves Saint Laurent, Burberry, Bentley, BMW, Apple, and Microsoft to eBay, Google, Netflix, Pepsi, and Burger King—have updated their logos. Whatever was once unique or distinctive has been removed. Varieties of fonts and styles have given way to standard sans serif fonts barely distinguishable from one another. Sciomorphic designs, not just in branding design but in various forms of graphic design, have moved aside to make room for the terminally flat. This is not branding as much as it is blanding. Why anyone should be concerned with this case of “mere aesthetics” is perhaps debatable. But, to my mind, this process of shifting from the distinctive to the mimetically uniform reveals some significant things about a general resistance to depth in our time.

The glorification of banal design did not arise out of nowhere, of course. It strongly echoes a sensibility that has dominated the graphic design world, with echoes in other creative fields, since the beginning of the twentieth century. In the 1920s, the German typographer Jan Tschichold, still high on the aesthetics of Bauhaus and Constructivist design, began to formulate his soon-to-be influential thoughts on how best to work with typography. The most famous distillation of his philosophy was published in his 1928 book The New Typography. There Tschichold writes, “The essence of the New Typography is clarity. This puts it into deliberate opposition to the old typography whose aim was ‘beauty’ and whose clarity did not attain the high level we require today.” Note the language of necessity. The supposed contingencies of “ornamental type, the (superficially understood) ‘beautiful’ appearance” and “extraneous ornaments” had, for Tschichold, at last given way to a much purer and more suitable form.

A similar philosophy to Tschichold’s was put forward soon after him by the British design scholar Beatrice Warde in her famous 1930 essay, “The Crystal Goblet, or Why Printing Should be Invisible.” Warde stresses that the best typography should not draw attention to itself. Its chief purpose is to communicate, not to be admired. The title of Warde’s essay comes from a metaphor. She compares two wine goblets—one of solid gold and heavily decorated with exquisite patterns and the other of simple, delicate, and transparent crystal glass. A “connoisseur of wine” is naturally interested in the wine and not the goblet. She picks the crystal goblet since it best reveals what it contains. Similarly, Warde argues that nothing about the design of typography should interfere with the meaning of the words. She believes it is possible to remove mediation almost entirely.

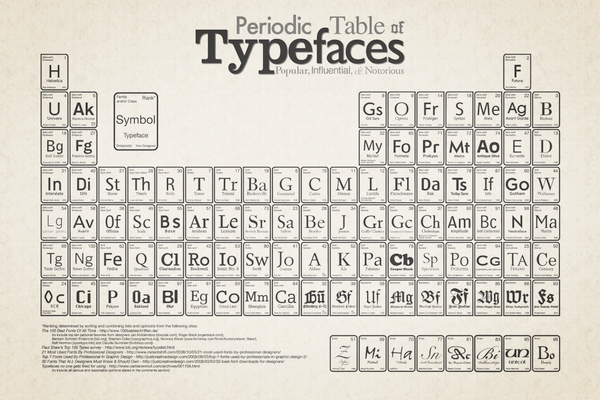

The thinking of Tschichold and Warde has shaped our world in ways we may not realize. The use of uncomplicated fonts like Johnston Sans for the London Underground or Parisine for the Paris Metro or Din on South African road signs reflects this same philosophy. Such a philosophy is evident everywhere: in typography, in graphs, infographics, websites, and logo designs. As Philip Meggs shows in his book A History of Graphic Design, so many movements in design, including the International Typographic Style (which gave us fonts like Helvetica and Univers), The New York School, American typographic expressionism, and a host of others, carry traces of this thinking and unthinking. Such a philosophy strongly intimates what the philosopher William Desmond calls the “univocal mind” that insists on being able to take things “at face value”—typically for strictly utilitarian purposes.

Arguably, the widespread governmental elevation of clear statistics over existential concerns in the current pandemic echoes the same preference for univocity over other modes of mediation. While typographic fashions drift occasionally towards incorporating more decorative elements, the standard in graphic design schools across the globe even today remains closely allied to the proclivities of the Tschicholds and Wardes of the world. On the whole, following the title of Adolf Loos’s famous 1908 essay, ornamentation has become criminal. As Loos explains, “I have discovered the following truth and present it to the world: cultural evolution is equivalent to the removal of ornament from articles in daily use.” Was the destruction of any reference to nature and incarnate being really so inevitable? For Loos, there’s a difference between art and utility, and utility was destined, by some accidental process called “evolution,” to win.

Considering this approximately a century after Tschichold and Warde and Loos formulated their philosophies, it is striking to note how history has repeated itself. Clinical approaches to design first appeared in the wake of the Romantic period, which was hardly ever ashamed of its love for the extraneous, since it echoed nature’s generous adornments. Serifs and blackletter typefaces were welcomed because they recalled the handiwork of stone carvers and calligraphers. Of course, we find many references to more embodied design in our time, in postmodern pastiche and hand-lettered digital type. But even there, the trend has become to remove any sense of historical and phenomenological reference in favor of endless replicability and meme-ability. How many people today know that serifs on fonts, like the one used in this article, developed because stone carvers found it neater to complete letters with a subtle flourish rather than too abruptly? The form emerged from the craft itself, not from some purely abstract decision-making process. Once it was the situatedness of typographers within the real world that shaped their actions. Now, the precise opposite seems to dominate visual forms. Alienation from the world has been normalized as the typical point of departure for design work.

A further similarity between early twentieth-century typographic design and typographic trends now is found in a set of troublesome philosophical presuppositions, all geared towards what design theorist Robin Kinross calls the “rhetoric of neutrality.” The point is that the many who have championed so-called neutral design have operated according to a strict modern mythos, which holds that it has no mythos. Contrary to what we might expect, neutrality is still rhetorical. The trouble is that, by opposing any mythos (or rhetoric), the operating mythos goes underground; it moves into the unconscious. What was once a highly mediated decision is soon taken as given. Mediation is forgotten. The mythos beneath the preference for univocal clarity is rooted in the idea that it is automatically less biased than any alternative. One can imagine this as a kind of aesthetic “blank slate” that operates on the belief that the mind is, apparently, interfering less when the result is less ornamental. The truth, however, may even be the opposite. As any designer knows, the simpler any result, the more decisions had to be made to construct it.

A further clue into the nature of this suppressed mythos as it functions in the bland design of today can be located in the ideas of Loos, Tschichold, and Warde, albeit more starkly in the work of Warde, as Stephen Eskilson suggests by referring to “digital crystal goblets.” The aim is to dissolve, if not annihilate, any sense of the origins of typography in human intentionality. In Warde’s time, the supposed “invisibility” of typography was supposed to serve a revealing function. This is still perhaps part of the contemporary design mythos but with a dramatic difference. What Warde wanted to reveal was what the text actually said. Typography was supposed to let language speak. Now, the transparency of type—an echo of what the philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls the “transparency society”—serves a much more insidious function. There is, so the mythos of transparency now declares, no depth behind bland aesthetics. The digital crystal goblet sacrifices meaning by refusing depth. Behind this shift towards total transparency is an often unacknowledged belief that information does not need to have any link to being. In an attention economy like ours, what matters is simply the fact that attention is paid, not whether that attention has any quality. The goblet is crystal—and empty.

This is nihilistic aesthetics. It is echoed in the “smooth” aesthetics of our technologies and the slick thought-free realm of user-interface designs. It is part of a growing anxiety over the link between intention and design, and thus a growing skepticism towards the possibility of design itself. After all, the very word design, as in its sibling-word designate, implies purpose and decision. And yet, the rise of digital culture has rendered this idea problematic. User experience designers, and arguably also their audiences, want things to work intuitively, which is to say compulsively. The person, when confronted with the seemingly obvious, should not be given time to pause and think but should rather simply react. The banal becomes a way to further entrench people in what Edmund Husserl called the natural attitude—without the possibility of reflective awareness. Ornamentation, or any aesthetic difference on display, functions too negatively to allow such compulsive reactivity. Blanding, in this way, denies agency and thoughtfulness to persons. To put it perhaps too strongly, it denies personhood to persons.

It is at this point that I want to mention one crucial theological implication to this shallow, albeit implicit, design philosophy. Linked to the growing depersonalization in typographical design, there is a profound trend towards anti-sacramentality. Univocal blandness and flatness are easily slotted into the world of rapid marketability. The point is not contemplation but consumption. It is not just being that is denied but being as the presence of real otherness. Glorifying the apparently obvious becomes a way of warding off the transcendent, since distraction—made much easier via friction-free, disembodied typographic banality—becomes the primary mode of attention.

Letter R from an 11th or 12th century copy of The Letters of Dunstan and the Life of St Dunstan (British Library)

In saying all of this, I am not necessarily gesturing towards a new philosophy of style. In essence, I simply want to draw attention to the fact that even so-called neutrality in the aesthetic realm today is loaded with significance—more significance than I have been able to cover here. Even if the philosophy that first gave rise to it has been forgotten, traces of it are not too difficult to find. What is fairly unique in digital crystal goblets and blanding and flattening, however, is the fact that style is apparently without any metaphysical referent. We have entered an age of typographic narcolepsy, in which embodiedness, situatedness, and ultimately being itself are all forgotten. Even if this does not cover every trend in the design world today, it is a worrying sign of a world obsessed with smoothing out all surfaces so that we can more easily take everything for granted.

Duncan Reyburn is an Associate Professor in the School of the Arts, University of Pretoria. He is the author of “Seeing Things as They Are: G. K. Chesterton and the Drama of Meaning.”