Art and the Restoration of the Value

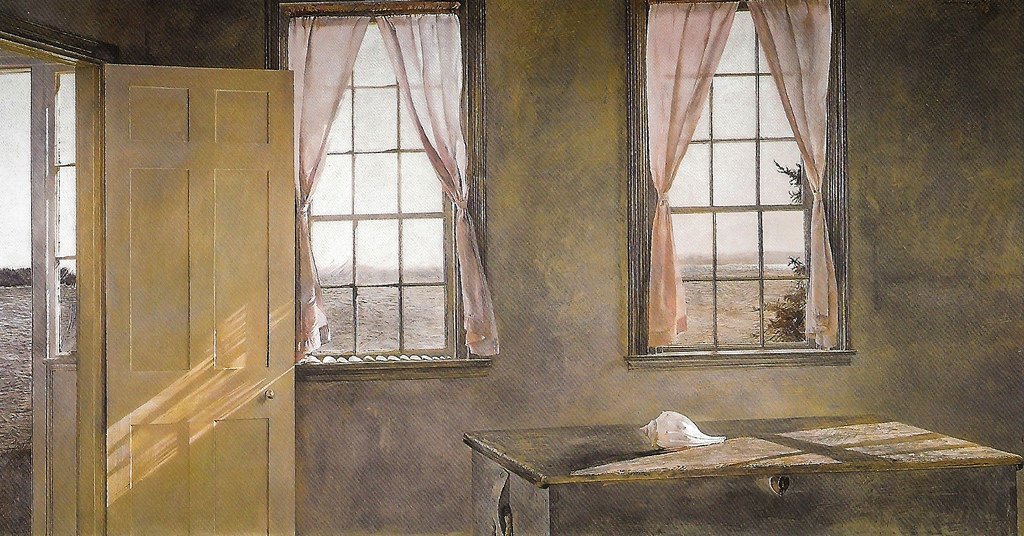

Andrew Wyeth, “Her Room,” Farnsworth Art Museum

I’ve never really liked talking about art in terms of value, because the first word that pops into most people’s heads is beauty—a word that makes it impossibly easy to pronounce judgment on a work on the basis of a passing glance and the registration of some vague visual pleasure, with no need to engage the substance of the work at all. And then there’s the idea of “family values” that works of art are sometimes seen to encourage or discourage. Like Pavlovian signals to an audience of brutes, this set of criteria often uses the coarsest of critical categories to praise facile works that flatter a prudish sensibility and damn difficult works that I often find convincing in some essential way, even if they’re problematic.

Talking about art in terms of value also opens up the critical discourse to auction prices and box office sales, to poll or survey data, psychological testing, cost-benefit analyses, and untold other metrics that measure art and give it a valuation which passes right over anything that might happen in the space between a work of art and a person who is touched by it, moved by it, or even changed by it. That is, all of these ways of connecting art to value jump right over the only thing that I could possibly care about in a work of art: its potential to enter my life, to become part of me, and to change the world that I see and act in in deep and abiding ways. So when I was leafing through Simone Weil’s Late Philosophical Writings and stumbled on her 1941 essay “The Responsibilities of Literature,” all of her talk about value initially put me off. But there was something else afoot in the essay—some concept of value distinct from those I mentioned above, and which leads her to press beyond questions about whether art has, encourages, or reinforces some determined category of positive or negative value to a question about whether art is bound up in the very existence of a concept of value in a culture at large. Weil writes:

The essential character of the first half of the twentieth century is the weakening and near disappearance of the concept of value. This is one of those rare phenomena that seems to be, as far as anyone can tell, something truly new in human history. It could have happened before, of course, in the course of some period that has vanished into oblivion, as could become the case with our time. This phenomenon has been seen in many areas outside literature, indeed, in all of them . . . But writers used to be the guardians of the treasure that has been lost, and a number of them are now proud of that loss.

Beyond identifying the disappearance of the concept of value and noting the active part played by some authors in applauding its disappearance, Weil goes on to claim that words used to talk about value have gone missing or have acquired severely degraded uses, the responsibility for which she places on writers:

What has happened to words renders sensible the progressive vanishing of the concept of value, and even though this fate of words does not depend on writers, one cannot help but hold them particularly responsible, since words are their job.

This statement gave me pause. Because although I was resistant to the straightforward idea that art’s relation to value lay merely in praising good things and condemning bad ones, I could sense a deeper question in Weil’s claims that seemed more promising. Maybe it was the stirring of a thought about how perception, and indeed all thinking, involves a perceived or implied value not as an added price tag arbitrarily assigned to an otherwise inert object, but as somehow constitutive not only of perception and human thought but of reality itself. A thought that maybe value wasn’t something that some things had and others didn’t, but that it was somehow an elemental ground woven into the bedrock of the world we inhabit.

It is, of course, an ancient and typically religious idea to think this. In the Book of Genesis, when God creates the world, he looks at it and sees that it is good. He sees in all things that are in creation an objective quality that they all share: goodness, and goodness is value. Goodness can be predicated of everything, however you want to cash that out. It’s a much later development in the history of philosophy and culture to suppose the opposite—to claim that value does not inhere in everything around us all of the time, but to argue that what value we humans see is merely our own construction, applied post hoc to creation and the various arrangements and rearrangements of atoms and molecules that constitute human life.

I fell deeply in love with Wallace Stevens in graduate school, and he was the poet of just this kind of vision of reality. The poetic project in so many of his philosophically oriented poems is to build up a sense for a mute, valueless, meaningless world within which we build our card houses of meaningful existence. For instance, in the 1934 poem “The Idea of Order at Key West,” the speaker observes of a singer singing by the water that she “sang beyond the genius of the sea,” insisting that despite the fact that the song was somehow related to the sea—“it may be that in all her phrases stirred the grinding water and the gasping wind”—it is only the song that the speaker hears: “it was she and not the sea we heard.” Cast against a backdrop of “meaningless plungings of water and wind,” the speaker grants all value-making in what he hears and sees to the singer’s artifice:

It was her voice that made

the sky acutest at its vanishing.

She measured to the hour its solitude.

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang. And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

that was her song, for she was the maker.

Stevens draws out this world devoid of anything but what a chemist might attend to—the spinning out of uncountably many unseen elemental forces determined by ironclad, heartless material laws. He says, “meaningless plungings of water and wind,” but truly that’s too poetic for what he’s gesturing toward—essentially a vision of the basis of reality as an unmade and therefore totally valueless collection of unrelated and unrelatable bits of fluff that coagulate and disintegrate in patterns we have come to recognize and that are useful to us for whatever reason. There’s no value in the world as such, only value that we construct on top of it.

The thing about this idea is that, even more in our time than in Weil’s, it has taken on the character of an axiom, a self-evident assertion about the world that all thinking people share. The idea was headed in that direction in 1941 when Weil wrote the essay, but in the aftermath of the fall of France to Germany, what might have seemed like a benign, highly intellectual revision of an old-fashioned way of looking at things suddenly started to look anything but harmless. Heated discussions took place in the leading literary magazines of the time about whether writers were responsible for the fall of France, and it was in the context of this discussion that Weil wrote the essay.

It’s not surprising that much of this discussion took place using the ways of talking about value that make me uncomfortable, and that claims that writers were responsible for the fall of France would have appealed to moral platitudes and rigid ideas of what literature should look like, nor is it surprising that most of the serious artists of the day revolted against these accusations. But Weil’s assessment of the problem digs underneath the surface-level disagreement, seeing in the loss of the concept of value a serious problem, a problem Weil goes so far as to claim is “the affliction of our time”—a problem that is both deeper and wider-reaching than a lost military campaign and which extends beyond France “to Europe, to America, and to other continents wherever Western influence has penetrated.” It is perhaps worth noting that today it is precisely in these places that a totalitarian mindset in response to the pandemic is once again rearing its head.

J.M.W. Turner Sunset Over a Lake

In the face of the Nazi terror, consumed by a sense of the dissolution of culture full stop, Weil reaches for a vision of what would be necessary to reverse it. Here she distances herself from the easy answers offered by conservative critics for whom the problems are so unproblematically clear, with a bold proposal for what an art of the future would need to be to truly set culture on a better track:

If our present suffering ever does lead to a moral reorientation, it will not be accomplished by slogans, but in silence and moral loneliness, through pain, misery, terror, in the deepest part of each spirit.

If the loss of value is the affliction of our time, and if the recovery of value is going to be this serious and this painful, but also this absolutely necessary, then we will need to dig very deep into the heart of the artistic enterprise to find the thing that has gone missing.

Tom Break is an artist, critic, and editor at In the Wind Projects.